ED's Policy-Based Evidence Making

Exploring the Gainful Employment claims on alternative programs & transfer options

Was this forwarded to you by a friend? Sign up, and get your own copy of the news that matters sent to your inbox every week. Sign up for the On EdTech newsletter. Interested in additional analysis? Try with our 30-day free trial and Upgrade to the On EdTech+ newsletter.

On March 31st of last year I wrote what has become a painfully prophetic view of the Biden Administration’s Department of Education (ED) and its regulatory approach.

We all knew that the US Department of Education (ED) would change its regulatory approach with the new administration, and it has been virtually axiomatic that they would directly target the for-profit sector. But recently it is becoming more clear the approach and scope of the ED regulations, and it can best be described as regulatory activism, by which I mean using the regulatory processes to achieve pre-defined end goals. And those goals seem to have a common “protect students from the bad actors” theme, usually based on the involvement of for-profit companies – and not just in the for-profit sector. Some people applaud the changes as overdue corrections to the system, and others decry the changes as overly broad and likely to have unintended consequences, but either way, I think those involved in online education and alternative models should take notice and avoid assuming that only the for-profit sector will face aggressive regulations.

There is one aspect of regulatory processes that I think deserves its own analysis. ED’s (and the Arnold Ventures coalition’s) activism could be characterized by the move from evidence-based policy making to policy-based evidence making. There has always been some level of using data to serve pre-determined end goals, including in the Trump and Obama administrations, but neither comes close to what we are seeing currently.

Gainful Employment Example

To get but one view into this tendency to create and describe data to serve a desired policy of protecting students from predatory actors, let’s look at one table from the final Gainful Employment (GE) & Financial Value Transparency (FVT) rules.

ED released the formal version of the rules over the weekend (i.e., publishing in the Federal Register and not just through a press release), although it is dated for tomorrow, October 10th.

One of the central claims by ED is that students in failing GE programs will not be overly-impacted, as “the majority of students have similar program options that do not fail the D/E rates or EP measure and are nearby, or even at the same institution.”

Table 4.25

The specific data table in the final GE & FVT rules to back up this claim is 4.25 in the Regulatory Impact Analysis.

Table 4.25 reports the distribution of the number of transfer options available to the students who would otherwise attend GE programs that fail at least one of the two metrics. [snip]

Let’s explore each part of this claim.

External Research

ED states that this data analysis is backed up by external research, unsurprisingly funded by Arnold Ventures (Stephanie Cellini is funded through a center at George Washington University and through Brookings).

These analyses are supported by external research, suggesting that most students in institutions closed by accountability provisions successfully reenroll in higher performing colleges.[89]

That report is worth reading, but it is fairly weak in being used to back up ED’s claims, as it is a different context.

The Cellini, et al report is based on sanctions from the 1990s and does not include effects of the modern for-profit industry nor of Gainful Employment.

The Cellini report is based on institutional sanctions whereas the GE rules are based on potential sanctions on specific programs.

The Cellini report data is largely centered on sanctions to 2-year for-profits and community colleges whereas current GE programs apply primarily to 4-year for-profits (certificates and degrees) and 4-year non-profits (certificates only).

The Cellini report is based on a statistical model of institutional enrollment trends with no tracking of actual students whereas the current GE claims are about real students finding alternative programs.

2-digit CIP Codes

ED uses “estimates for four different ways of conceptualizing and measuring these transfer options.” The first, third, and fourth columns are based on 2-digit CIP codes, which present an arbitrary replacement mechanism that does not represent vocational programs (the primary target of GE rules). Take, for example, CIP 51 Health Professions & Related Clinical Sciences. That is not how students choose programs; rather, they choose at a lower level of detail for 4-digit CIP codes or even 6-digit CIP codes. Furthermore, vocations from actual hiring organizations are much more specific than this high level.

Arguing that Veterinary Medicine is a replacement or “transfer option” for Dentistry or Allied Health Diagnostics, Intervention, and Treatment Professions is ludicrous unless one is just looking for data to back up a desired policy.

The second column “Same Zip3, credlevel, CIP4” is worth taking more seriously, based on this specific claim:

Two-thirds of students (at 60 percent of the failing programs) have a transfer option passing the GE measures within the same geographic area (ZIP3), credential level, and narrow field (4-digit CIP code).

Passing vs. Non-failing

First of all, this language is just wrong. The data calculate a replacement program as “non-failing” and not “passing”. ED only calculates the metrics for program cohorts (either 1-year or 2-year) with 30 or more students, for privacy reasons primarily. Programs that pass have data available and pass both metrics (debt-to-earnings and earnings premium). Non-failing programs combine passing with those programs that have no data.

Table 4.9 (bottom row) shows that fully 87.7% of GE programs do not have data. We have no idea if these programs are better or worse than a failing program - there just is no data. These 87.7% of no-data GE programs have 36.3% of all GE program enrollments.

What the GE & FVT rules do is consider a non-failing program as a valid replacement for a failing GE program, and the majority of these programs have no valid data.

Same Zip3

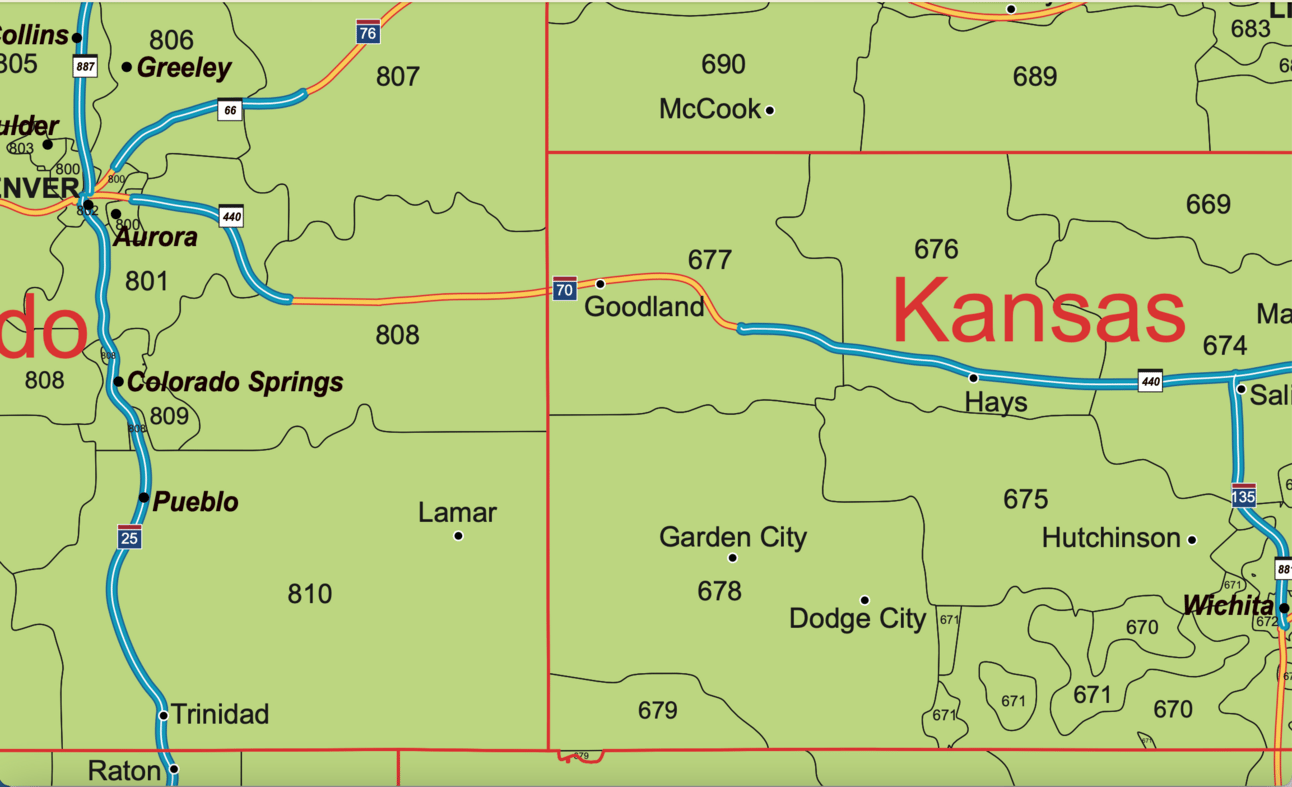

ED considers programs in the same Zip3 (the first 3 digits of a zip code) as being in the same geographic area, and therefore as a realistic transfer option for students at failing GE programs. Is this a realistic measure of geographic proximity, where a student may commute to a different institution? In the vast majority of locations, No.

Let’s look at a fairly crowded area, where Zip3 measure of proximity may be appropriate.

Zip3s of 220, 221, and 225 are probably realistic in terms of a student transferring to a geographically close replacement program.

But in most of the country, Zip3 is a terrible metric to capture geographic proximity.

Pueblo, CO to Lamar, CO in the same Zip3 is a distance (one-way) of 122 miles. You can see that Colorado Springs is closer, but actual distance is not the metric used by ED. Zip3 does not address geographic proximity realistically.

Same Credential, Same CIP4

These metrics make sense. Students seeking the same credential (e.g., associate’s degree, bachelor’s degree) and within the same CIP4. CIP6 would be better, but CIP4 is realistic.

But One Example

Note that this is but one example of how ED (and allies) set policy first and then look for data - even misleading or partial data - to back up that policy. I haven’t even included the issue of whether a program with 11 students can take in 500+ transfer students, or how certain states would lose 100% of specific program types. This post is based just on Table 4.25.

This topic may seem wonky, but consider the implications. By ED’s estimate, there are nearly 700,000 students at GE programs that would currently fail, losing their ability to receive financial aid. ED waives off the impact based on Table 4.25 and a don’t worry, the majority of these students will find something better attitude. But the data do not actually back up these conclusions.

ED’s own data show that 40% of students in failing GE programs (roughly 280,000) do not have a viable transfer option. If ED is wrong in the analysis (as I believe it is), it is likely that 400,000+ of mostly minority and female students are likely to lose access to their chosen program with no reasonable alternative. And several industries - especially in mostly rural states - will lose most or all viable vocational education options.

I’ll go back to my March 2022 post and it’s conclusion.

Put these together and I see what appears to be a common approach.

* Use regulatory processes not just as safeguards but also to enable predefined end goals, usually around ‘reining in for-profit’ entities;

* Minimize the amount of time allowed for public comment and debate;

* Informally work through multiple agencies, both federal and state, to set new rules; and

* Worry about the unintended consequences later.

To this I would add: “Find the data, even with flawed assumptions, that makes it appear that the pre-defined policy makes sense.”

The main On EdTech newsletter is free to share in part or in whole. All we ask is attribution.

Thanks for being a subscriber.